Understanding Hunger During a Pandemic: A Brief Overview of Federal Nutrition Programs

Since the school closures and stay-at-home order began in late March, I have been volunteering at food pantries in my hometown of Athens, TN where approximately 29 percent of the almost 14,000 residents live below the poverty line. It took less than a month for hundreds of cars and socially distanced people to gather outside. As the weeks passed and participation rates rose, the image of people waiting in a single-file line that I once associated with amusement parks, school cafeterias, or even the drive thru at a popular fast food joint morphed into something decidedly cruel.

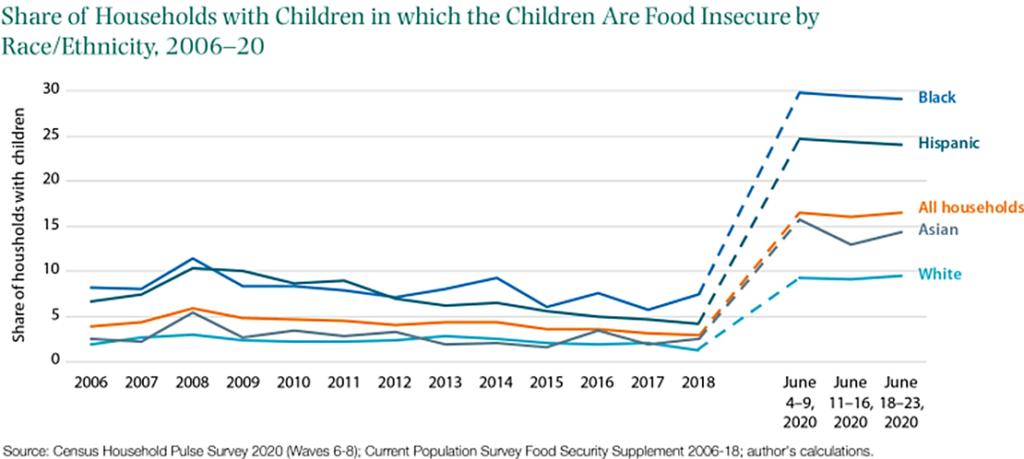

In these lines, we see historic and inhumane levels of food insecurity. Recent data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey indicates that 31 percent of respondents with children were either uncertain about or unable to get enough food for everybody in their household in late June. This percentage should not be confused with Figure 1’s depiction of child food insecurity, a more extreme form of hunger in which parents do not have enough resources to buffer their children from deprivation. The Brookings Institute finds that 13.9 million children lived in a household characterized by child food insecurity in late June, which is 5.6 times as many as in all of 2018 (2.5 million) and 2.7 times as many than did at the peak of the Great Recession (5.1 million).

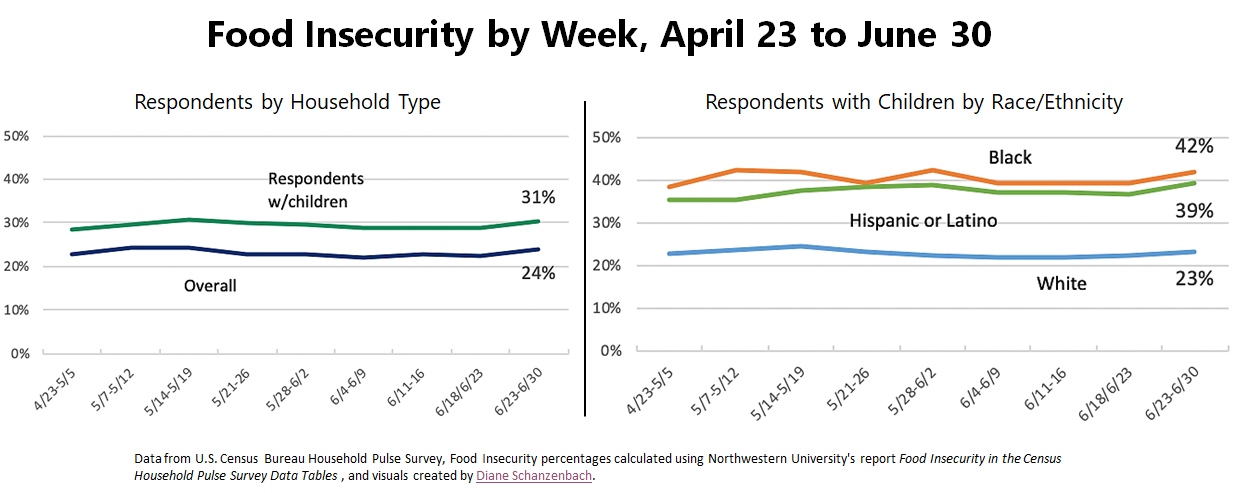

This level of need is untenable for many food pantries, even with the relative success of programs meant to connect local producers to food redistributors like the Farmers to Families Food Box Program.[1] In fact, rates of food insecurity have more than doubled since late March, with an alarming 42 percent of Black households with children sometimes or often not having enough to eat at the end of June compared to 23 percent of White families (Figure 4). If pre-pandemic trends are any indication, we can assume that Black single mothers and their children are disproportionately bearing the burden of these racial inequities.

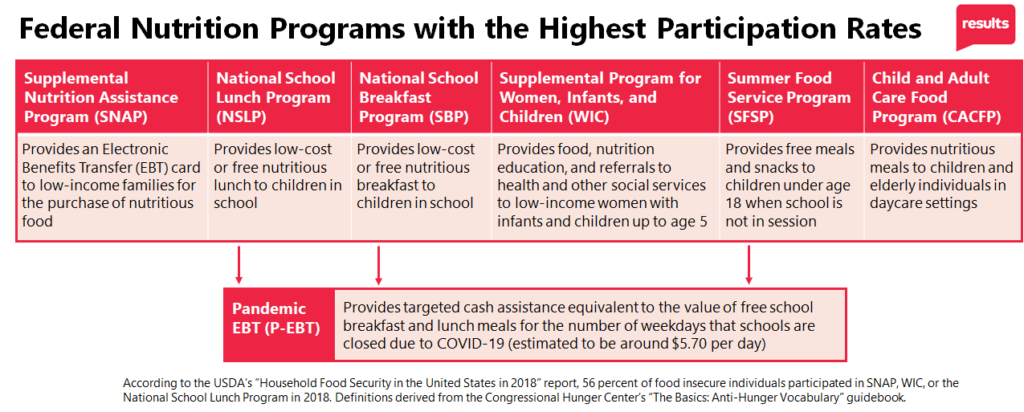

Figure 2

At a time when the number of people served at food banks has increased more than 50 percent from a year ago, it is jarring to remember that only 1 out of every 10 grocery bags that feed people who are hungry come from charitable organizations. The rest comes from federal nutrition programs. Of the federal nutrition programs with the highest participation rates as listed in Figure 2, the Supplemental Nutrition Program (SNAP) casts the widest net, offering benefits in the form of an Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) card to childless workers, seniors, and people with disabilities living on a fixed income as well as low-income families. The remaining six, including Pandemic EBT (P-EBT), aim almost exclusively to improve child food security.

Although effective in stabilizing the federal poverty rate through a $600 boost in weekly unemployment benefits and a one-time stimulus check, the CARES Act included few provisions that strengthened our federal nutrition programs. Here are the major actions that the federal government has taken in support of low-income families struggling to put food on the table as of mid-July[2]:

- SNAP Emergency Allotments (EAs): All SNAP households eligible for less than the maximum benefit due to reportable income, assets, or other factors receive emergency allotments (EAs) to bring them up to the maximum. For the average 5-person household who received $528 in SNAP benefits before the pandemic, this allotment adds $240 to their monthly benefit level, raising the total benefits received to $748. Approximately 40 percent of households who already received the maximum benefit—families and individuals with the highest need before the health crisis—did not benefit from this provision. States can continue to apply for these supplementary benefits month-by-month if the federal government has declared a public health emergency and the state has issued an emergency or disaster declaration, but some states officially ended this boost in benefits on June 30th.

- Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT): This program targets households with children who would otherwise receive free or reduced-price meals if schools were not closed due to the pandemic. In practice, the value of free school breakfast and lunch meals (estimated to be about $5.70 per day) is loaded onto an existing or new EBT card, replacing meals lost during the 2019-2020 school year. It is important to note that these benefits can be issued retroactively in cases where states experienced delays in implementing the program or if a student gained eligibility for free or reduced meals after school closures began. States are not authorized to provide P-EBT benefits over the summer or during holiday breaks, and Congress has yet to reauthorize states to reboot the program in any case where a school is closed for 5 consecutive days in the 2020-2021 school year. For more information on how P-EBT operates by state, visit frac.org/pebt.

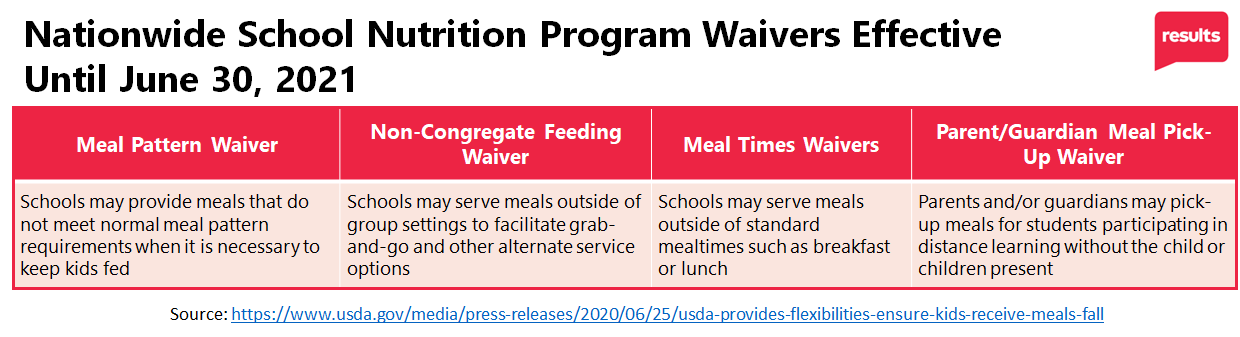

Additionally, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has issued waivers that ease cumbersome administrative rules, reduce barriers to access, and provide the flexibility needed to honor social distancing measures while still redistributing food. For example, community organizations that run the Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) were given permission to deliver meals directly to the homes of low-income children as well as operate grab n’ go meal pick-up sites. Many of the same waivers that made these innovations to the summer program possible have been extended to June 30, 2021 for the National School Breakfast and Lunch Programs (SBP and NSLP) and the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP), as described in Figure 4.

Figure 3

It is evident to me that Congress and the administration recognize the ability of federal nutrition programs to adapt to fluctuations in need, yet little has been done to strengthen these high-impact programs since the passage of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) in mid-March. Approximately 40 percent of low-income households with the highest need prior to the pandemic still have not seen an increase in their SNAP benefits, and discriminatory eligibility rules continue to bar undocumented immigrants and people with criminal records from assistance in most states.[3] Four waivers to allow meal sites more flexibility this school year are a helpful but not nearly sufficient federal response, especially when small community organizations lack the infrastructure to meet this historic demand (Figure 4).

Figure 4

RESULTS and other organizations have repeatedly called for a 15 percent increase to the SNAP maximum benefit, which would get money to the poorest households and generate between $1.50 and $1.80 in economic activity. Participants spend their benefits quickly, with positive impacts felt up and down the food chain—from farmers and food producers, to grocery retailers, stock clerks, and local economies. It is urgent that Congress act now to provide (1) a 15 percent boost in the SNAP maximum benefit that would help all SNAP households, (2) an increase in the SNAP monthly minimum benefit from $16 to $30, and (3) a suspension of work requirements, time limits, and cumbersome adminstrative rules.

Because of P-EBT’s wide eligibility, including any household with a child that receives free or reduced lunch at school regardless of citizenship status, it is imperative that the program be extended through the summer and sustained for years to come. Research shows that in a typical year, families cannot absorb the loss of the value of school meals in the transition from the school year to the summer, and the Summer Food Service Program (SSFP), which provided meals to less than 10 percent of the children eligible for free or reduced lunch in 2019, does not reach nearly enough families. The P-EBT program has the potential to reach all children missing out on meals provided through the federal nutrition programs at school as well as those whose families do not qualify for SNAP.

The longer Congress waits to pass another relief package, the longer we fail to feed our communities. Under no circumstance should I be telling hungry people waiting in 90+ degree heat for a sack of canned meat, protein bars, and week-old bread donated by the local supermarket: “We ran out of food.”

By Jessi Russell, 2020 Zero Hunger Intern via the Congressional Hunger Center

[1] Under this program, farmers sell food previously destined for restaurants and bulk purchasers to large distribution companies, minimizing food waste. USDA then partners with these distributers to purchase, package, and transport family-sized boxes filled with fresh produce, dairy, and meat products up to $3 billion. Once the food boxes have arrived at local schools, food banks, faith-based organizations, families can come pick them up. The first round of purchases totaling up to $1.2 billion occurred from May 15 through June 30, 2020. The second round will aim to purchase up to $1.47 billion July 1 through August 31, 2020. After August, the program will effectively end as it reaches its $3 billion limit unless more funds are appropriated.

[2] Each of these programs, including the nationwide waivers, are contingent on states applying for and being approved to receive these benefits. The Center for Budget and Policy Priorities tracks state participation here.

[3] Some states have a lifetime ban on SNAP participation for people convicted of drug offenses, while others place restrictions on returning citizens if they are reported to be noncompliant with parole conditions, according to Bread for the World’s 2019 Racial Equity Report. It is also common for states to impose a period of ineligibility after release or require that all parole and probation requirements be met before a person is eligible. The restrictions jeopardize the food security of Black and Latino households seeing as the criminal justice system profiles, arrests, incarcerates, and sentences Black and brown people at a disproportionately high rate.