Strange Fruit: How Racial Inequities in Housing Contribute to Death in Black Communities

This year marks the 81st anniversary of jazz singer, Billie Holiday’s iconic recording for the song “Strange Fruit”, a haunting song that is both a lament and protest of the brutality of lynching of Black bodies. The song was adapted from a poem written by Jewish schoolteacher Abel Meeropol after seeing the disturbing image of two young Black teenagers’ battered bodies hanging from a tree surrounded by a mob of gleeful white civilians in Marion, Indiana.

Since Holiday’s recording of the song, “strange fruit” became a frequent reference to the lynching of Black people.

In modern times, the term “strange fruit” has come to represent the horrors and trauma of anti-Black racism more broadly. It illustrates the impact persistent racial violence in the form of both structural and physical racism has on Black individuals, Black families, and Black communities.

Structural racism continues to kill Black Americans at disproportionate rates. The concept of strange fruit is no more applicable to communities of color than in the aftermath of COVID-19 where communities of color are being disproportionately impacted. Research reveals that Black families face a higher risk of contracting and dying from the virus. Residents living in majority-Black communities have three times the rate of infection and six times deaths than that of residents living in majority-white communities.

One of the main factors that contributes to these rates is the lack of access to quality housing. While some would argue communities of color are still being physically lynched (e.g. George Floyd in Minnesota, Ahmaud Abery in Georgia, and Breonna Taylor in Kentucky), policies that perpetuate structural racism and undermine access to equitable and affordable housing are another form of racial violence have contributed to the disproportionate high mortality rates in Black communities. To examine the root cause of these racial disparities, we must look at the history of racial housing inequities in America.

Housing is a human right. This message has been reverberated time and time again by congressional members, housing advocates, and civil rights activists. This is the idea that the right to have a safe and quality place to live is not a luxury, but a meet human necessity. The question that remains is how can the idea of housing being a human right be applied to communities that have constantly been denied their humanity through the dismissal of their needs?

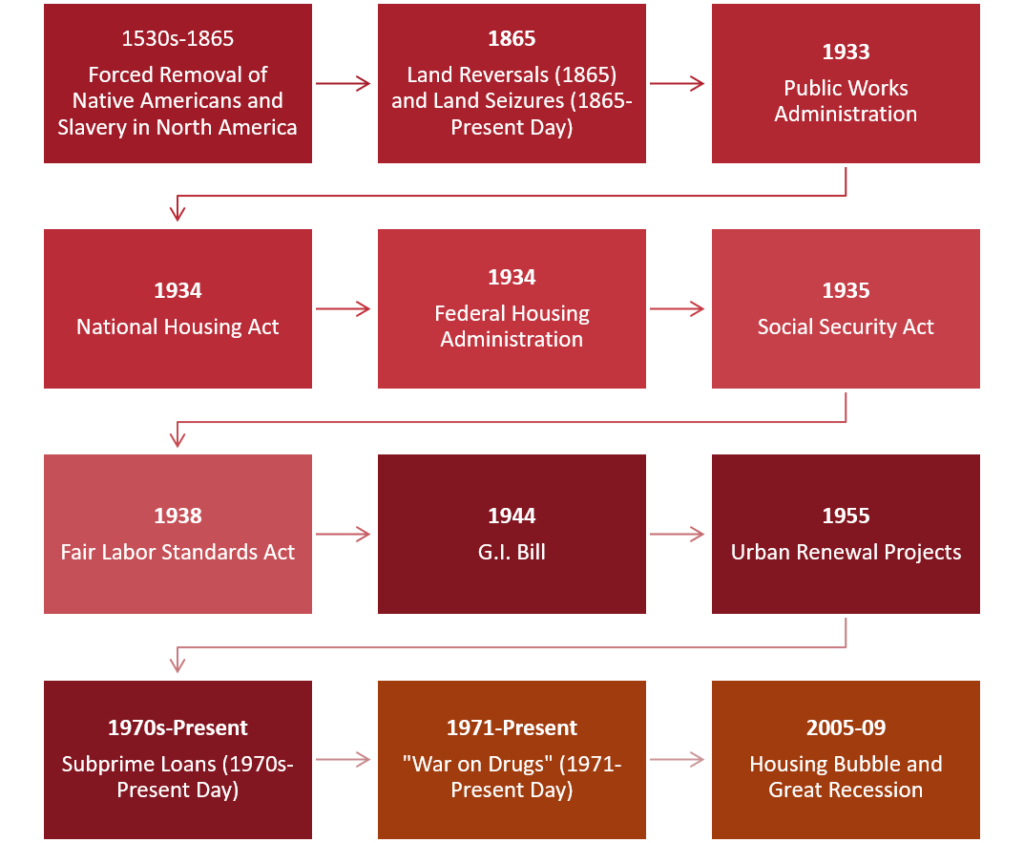

In the U.S., housing is vital to the economic wellbeing individuals, families, and communities. It is a means of security, access to opportunity, and mobility from poverty, something that the Black community has always been denied. Historically, barriers to affordable housing have always inhibited people of color’s ability to create racial wealth. Research points to the role of federal policies as the historical drivers of racial wealth inequality. The figure below depicts some of the major policies dating back to the Civil War era that laid the structural foundation for the racial wealth disparities present today.

Visual created by 2018 Emerson Hunger Fellow Funke Aderonmu, adapted from Bread For the World Racial Wealth Gap Simulation Policy Packet

These practices have had lasting impact on the state of wealth and housing inequality today. Structural racism in the U.S. housing system continue to contribute to stark and persistent racial disparities in wealth and financial well-being, especially between Black and white households.

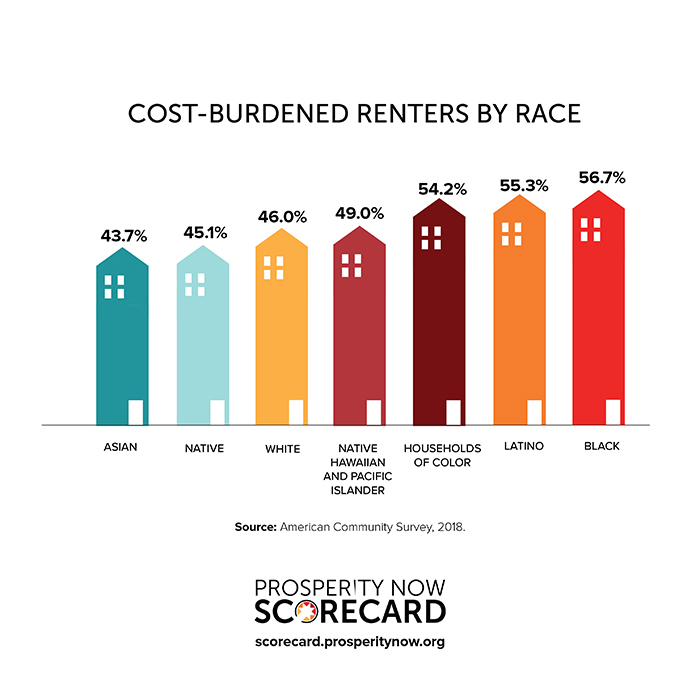

The housing market continues to be segregated along racial lines. Due to the legacy of racist policies, Black families and other people of color are more likely to be renters — 59 percent of Black-occupied housing units are rented as compared with 28 percent of non-Hispanic white-occupied housing units. Many renters of color were already struggling to afford housing (right) in the U.S. before the pandemic and were more likely to face evictions.

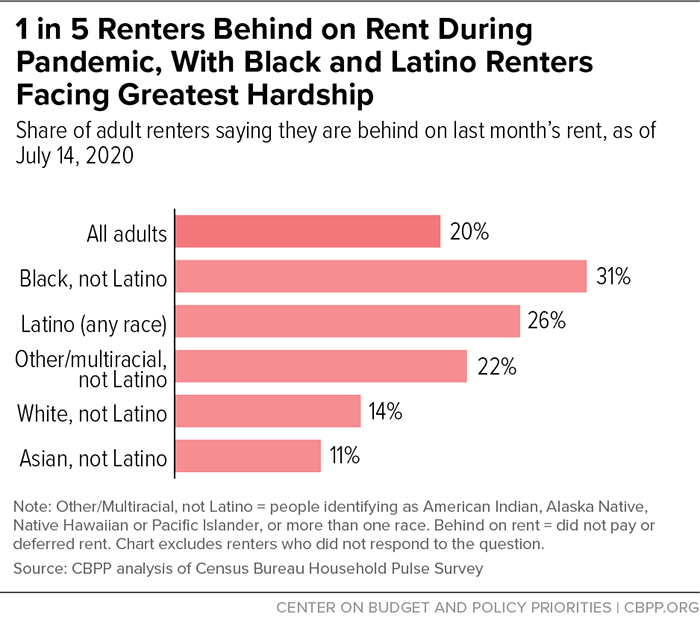

The pandemic has shown in stark relief that housing instability impacts Black Americans and people of color. 31 percent of Black Americans told the Census Bureau in early July that they had fallen behind on rent (see below) – a clear sign that the legacy of racist policies is harming Black renters right now.

Racial discrimination in real estate, lending practices, and federal housing policy have limited the homeownership rates of minorities. In addition, racial discrimination in the housing market continues to put Black homebuyers at a disadvantage in comparison to white homeowners. While under the Fair Housing Act, overt racial discrimination had decreased, more elusive forms of discrimination have become more prominent in the housing market. Racial steering and discrimination against Black home mortgage applicants have increased the housing and wealth divide.

To address this issue, it is important to have conversations with policy makers and urge them to prioritize policies that work to promote racial equity in housing. Lawmakers should support policies that prioritize wealth building for people of color and the expansion of rental assistance and affordable housing.