Federal policies make it harder for noncitizens to move out of poverty

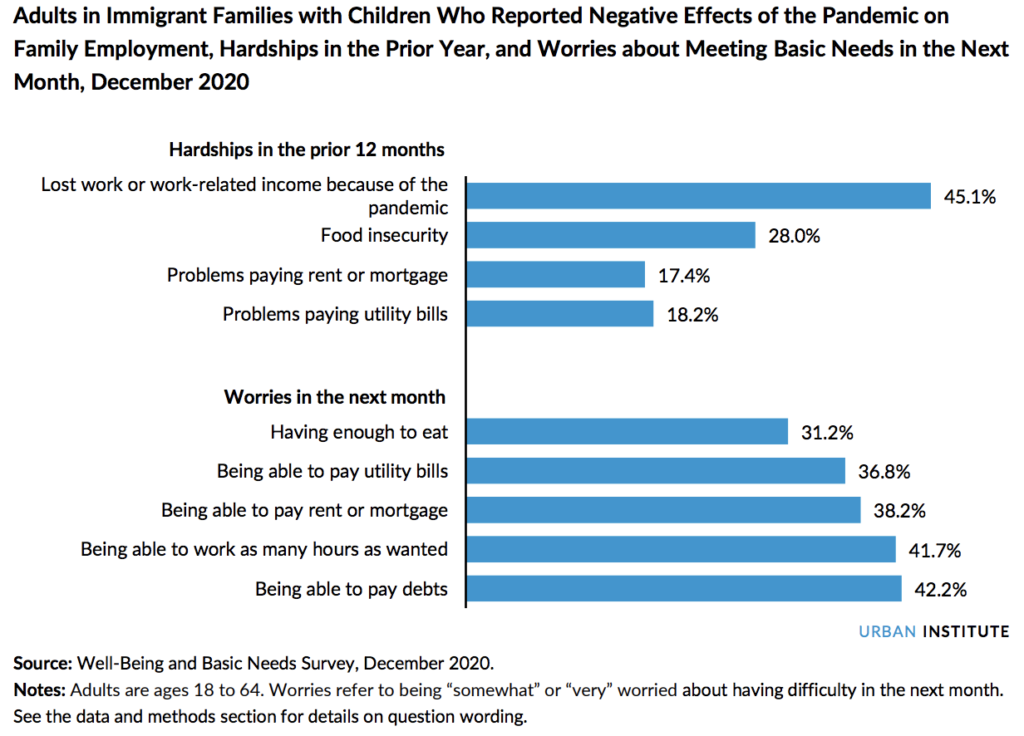

While the COVID-19 pandemic decimated the working class in the United States, many families turned to federal assistance programs for support to survive when things felt like they were falling apart. However, as the toll of the pandemic rose, the disparities between citizens and noncitizen residents widened astronomically. The results of a survey by the Urban Institute show how immigrant families’ experiences of hardship has been compounded by the pandemic. Over 30 percent of immigrant families reported worries about meeting their basic needs (Figure 1) in December 2020. The pandemic exposed the impact of xenophobic rhetoric at a national scale that has threatened immigrant communities and pushed them further away from asking for the assistance they need to survive.

Despite having some poverty alleviating resources provided to them, many immigrants avoid collecting government benefits because of immigration concerns, such as being prosecuted by Immigration Customs Enforcement (“ICE”) which can lead to deportation and family break-up (more below on how noncitizen participation in anti-poverty policies functions). The aforementioned survey conducted by Urban Institute found that 20 percent of adults in immigrant families avoided any noncash benefits out of fear. When focusing on low-income families, this percentage increases to almost a third. In regards to health, 8 percent avoid programs such as Medicaid and other free or low-cost medical care. Approximately 10.1 percent avoid food and nutrition programs such as SNAP, WIC, emergency food assistance and more. Finally, 7.2 percent avoid utilizing housing subsidies and emergency rental assistance.

These numbers appear small but they do not fully capture the fear noncitizens experience when accessing benefits. While some risk their safety and claim benefits anyway, the “chilling effects” experienced by many immigrant communities, that were exacerbated because of the Trump-era ‘public charge’ rule, can cause many community members to struggle against not having enough food, experiencing housing insecurity and more. Chilling effects can be explained as families avoiding benefits to assist with necessities because they are concerned about green card/immigration status or immigration enforcement. These chilling effects have been reported by 36.2 percent of immigrants in regard to housing. For health programs, 40.2 percent reported chilling effects. The highest reported area of these chilling effects are food and nutrition, where 50.2 percent of immigrants reported chilling effects. Noncitizen communities face the double burden of xenophobic anti-poverty policies and hyper-policing that have created the current levels of fear.

Qualifying for anti-poverty programs is exceedingly difficult for noncitizens.

There are many misconceptions and confusion about which noncitizens can access federal anti-poverty programs. Current practices limit access to some anti-poverty programs for certain immigrant and refugee populations, unfairly denying access to individuals without documents and many individuals who recently arrived in the United States. The misconceptions and confusion stem from the fact that noncitizen communities are divided into three categories when determining access to anti-poverty programs, with several exceptions (discussed below): qualified immigrants who entered before August 20, 1996; qualified immigrants who entered following August 20, 1996; and nonqualified immigrants.

In order to qualify according to the 1996 welfare reform, noncitizens must be at least one of the following:

- Lawful permanent residents (LPRs),

- Refugees or asylees,

- Cuban/Haitian entrants,

- Individuals granted withholding of deportation by U.S. Citizen and Immigration Services,

- Individual granted conditional entry to the country,

- And certain battered spouses and children.

For these ‘qualified’ noncitizens who arrived prior to the enactment of The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-193, also known as “welfare reform”), they are generally able to access anti-poverty programs in the same manner as U.S. citizens. Similarly ‘qualified’ noncitizens that arrived after former President Clinton signed the 1996 bill into law are required to wait at least five years after being granted their qualified status in order to access some anti-poverty programs. There are only rare circumstances in which individuals without documents or who fail to meet any of the above criteria are eligible to access federal anti-poverty programs.

Access to anti-poverty programs vary dramatically for different categories of noncitizens.

Under The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, “qualified” noncitizens were sorted into two categories, with those who entered on or after the legislation took affect facing new requirements to qualify for these critical anti-poverty programs. This law required immigrant families wait at least 5 years since the date that they were deemed a “qualified” noncitizen in order to access antipoverty programs.

There are some exceptions across many programs. For instance, victims of trafficking and their beneficiaries are eligible to receive benefits from several anti-poverty programs. However, these circumstances that would qualify otherwise ineligible noncitizens are exceptional and quite rare. Resultingly, the accessibility of these programs varies dramatically for different groups of noncitizens, as seen in the chart below.

| Programs | “Qualified” Noncitizen (Entered before August 20, 1996) | “Qualified” Noncitizen (Entered on/after August 20, 1996) | Not “Qualified” Noncitizen |

| Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) | Eligible under certain circumstances | Eligible after 5-year requirement or under certain circumstances | Eligible only in rare circumstances |

| Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) | Eligible | Eligible after 5-year requirement or under certain circumstances | Eligible only in rare circumstances |

| HUD Public Housing | Eligible EXCEPT some Cuban/Haitian Entrants | Eligible after 5-year requirement EXCEPT some Cuban/Haitian Entrants | Eligible only in rare circumstances |

| HUD Housing Choice Voucher and Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance Programs | Eligible EXCEPT some Cuban/Haitian Entrants | Eligible after 5-year requirement EXCEPT some Cuban/Haitian Entrants | Eligible only in rare circumstances |

| Supplemental Security Income (SSI) | Eligible under certain circumstances | Eligible if LPR has 40 quarters of work after 5-year requirement or under certain circumstances | Eligible if receiving SSI on August 20, 1996 or in rare circumstances |

| Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) | Eligible | Eligible under certain circumstances (with state options to expand to children under 21 and pregnant people) | Eligible under certain circumstances (with state options to expand to children under 21 and pregnant people) |

| Full-Scope Medicaid | Eligible | Eligible under certain circumstances (with state options to expand to children under 21 and pregnant people) | Eligible under certain circumstances (with state options to expand to children under 21 and pregnant people) |

Much like how families with noncitizens must jump through bureaucratic hoops to qualify for anti-poverty programs, they face similarly troubling requirements in attempts to access the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) or Child Tax Credit (CTC). These refundable tax credits help low-income workers and families by supplementing their income. Qualifying for these tax credits requires that individuals have a Social Security Number (SSN). That caveat, however, means that noncitizens who have Individual Tax Identification Numbers (ITINs) are not be eligible for some refundable tax credits like the EITC. Mixed-status families with children who have SSNs qualify for the CTC. Prior to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, families with children who have ITINs qualified as well. Since that legislation however, children with ITINs are unable to qualify for these powerful anti-poverty tools.

Advocates have called for these inequities to be address and for the information regarding the accessibility of tax credits be more effectively disseminated in immigrant communities. The SSN requirements for these tax credits force many noncitizen families to lose out on credits that they would have otherwise qualified for. These policies are xenophobic considering ineligibility singles out noncitizens despite the fact that they participate in American society like citizens by paying taxes, contribute their labor to the economy and deserve equal rights to critical benefits as well.

How we can fix these complex, xenophobic policies…

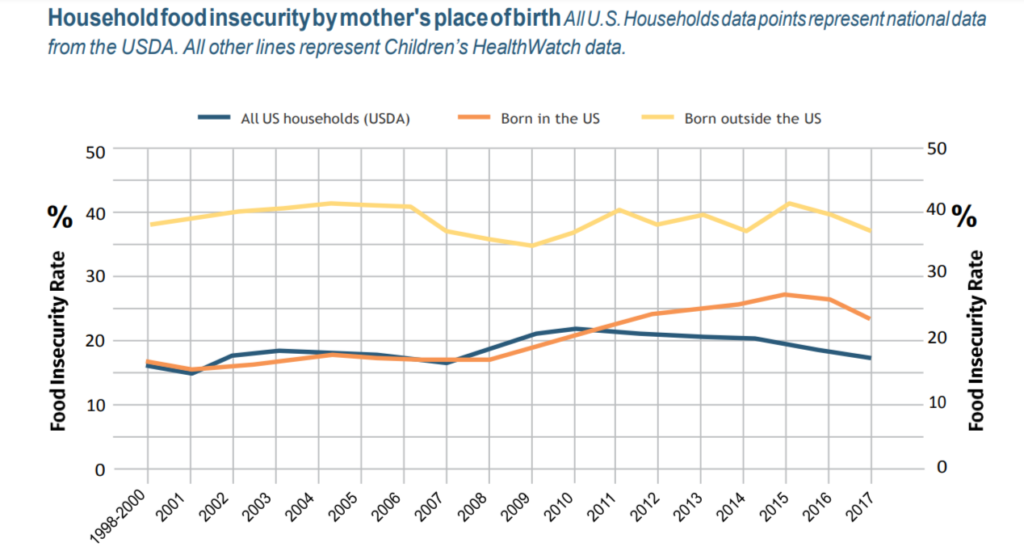

Ending poverty, which lies at the heart of our mission at RESULTS, requires expanding access to these key anti-poverty programs for noncitizen communities. Poverty does not care about immigration status. A study conducted by Children’s HealthWatch found that over 35 percent of families where the mother is foreign born experience food insecurity compared to less than 25 percent of families where the mother was born in the United States (Figure 3). Combatting these inequities between citizens and noncitizens requires re-evaluating access to federal anti-poverty programs for families with noncitizens.

Advocates have been calling for the end of anti-immigrant rules in public policy. The most recent success of this advocacy has been the Biden Administration’s decision to reverse the previous administration’s expansion of ‘public charge’. There is still a desperate need to effectively communicate this change and encourage noncitizens to access programs that would benefit them. Advocates have also suggested the federal government take the following steps to expand access for noncitizen communities:

- Expand access to federal anti-poverty programs for noncitizens. Current federal policy requires that noncitizens who arrived after 1996 wait 5 years before ‘qualifying’. This arbitrary timeline inhibits many noncitizen families from accessing programs that will keep their families from falling further into poverty, keeping a roof over their heads and food on their tables. Removing this five-year requirement would ensure all immigrant families can access programs when they need it. Additionally, further expanding the definition of ‘qualified’ noncitizen would enable more families to benefit from these programs. Allowing more noncitizens to access these programs would ensure that no families in the United States are suffering from poverty due to xenophobia codified in laws and regulations.

- Create pathways to legal immigration status, and eventual citizenship, for individuals without documents. Current laws and regulations make it exceedingly difficult and burdensome for individuals without documents to be able to access the federal anti-poverty programs discussed earlier in this piece. The xenophobic reasons for denying access to anti-poverty programs forces many families, even those with U.S. citizen children, to forgo desperately needed assistance in order to ensure the safety and togetherness of their families. The need to develop these pathways to citizenship are desperately needed now more than ever – particularly given the 50 percent rise in detentions of noncitizens by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) under President Biden between January and May 2021. Creating pathways to legal status and citizenship for individuals without documents will enable all families living in the United States to access the programs that they require to meet their basic needs.

- Remove stigma associated with anti-poverty programs. Even after the above steps are complete, there will continue to be many barriers for noncitizens and their families to access crucial anti-poverty programs. In order to further alleviate these barriers, the federal government should take steps to address the stigma connected with using anti-poverty programs such as cash assistance and SNAP. Moreover, taking steps to address the racialized stereotypes of who requires such assistance will further undo the harm suffered by noncitizens of color, who face the double burdens of xenophobia and racism. Ending this stigma will require coordinated efforts to re-educate the public regarding what federal anti-poverty programs are, the qualifications for such programs, and who are the people turning to such assistance. Undoing this stigma will further enable families in need, especially those with noncitizens, to engage with these programs and use them to keep their families from continued suffering in poverty.

Taking these actions will benefit families with noncitizens who crucially need access to these programs now during economy recovery from the fallout of the pandemic as well as in the future even when the pandemic ends. These steps are just the first of many needed to create long-lasting change for noncitizen communities and to end xenophobia in federal anti-poverty programs.

Noncitizen families deserve to know that when push comes to shove anti-poverty programs are available to them as well. Ending poverty demands that we end public policies that are riddled with xenophobic rules and regulations. Equitable inclusion of noncitizen families ensures that all individuals residing within the United States can access the anti-poverty programs that will keep their families housed, fed, and warm all year long.